May 22, 2021

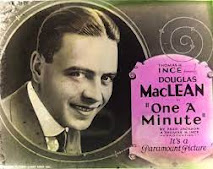

One A Minute –

U.S., 1921

In discussing Douglas MacLean’s 1921 film One a Minute, I’m tempted to paraphrase the tag of Billy Crystal’s 61* and ponder history’s rather peculiar judgment that there were only three great silent comedians of the male persuasion – Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd. The implication, of course, would be that MacLean deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as those cinematic giants, a suggestion that Kevin Brownlow had no qualms about making in his seminal book The Parade’s Gone By, but which I cannot support beyond the deep affection I have for his performance in One A Minute. See, fate saw to it that MacLean would be easy to forgot. Of the twenty-three feature films he made, only two survive in full. Our loss.

One A Minute,

directed by Jack Nelson, features MacLean as Jimmy Knight, a recent graduate of

law school returning to his hometown, Centerville, to run his father’s drug

store, and if that sentence doesn’t make your head spin, I’m not sure what

will. Like so many other trips home in silent films, this one allows two

attractive youngers, Jimmy and Miriam Rogers (Marian De Beck) to meet and

discover a comradery. Unlike other films, this bond involves an article on

Abraham Lincoln and his reputation as a fighter, a quality both of them admire.

As luck would have it, they both embark at Centerville, although not entirely

at the same time.

After a humorous bit involving Jimmy, a fancy car, and a

few local townspeople, Jimmy arrives at his father’s store to find it hemorrhaging

customers to a CVS-like competitor able to offer medicine at cheaper prices and

keep its shelves fully stocked. In fact, these days, its most loyal customer

seems to be Jimmy’s aunt, who according to the intertitles, has never read

about a condition she didn’t then discover she had. Soon, he’s cursing the very

store he came back to save and remarking to a reporter friend (Victor Potel)

how much he wishes someone would just walk in and offer him $1,000 for it. And

wouldn’t you know it? Within seconds of uttering those hopeful words, the doors

swing open and the owner of his competitor (Andrew Robson) enters offering to

buy him out for $2,000. There’s only one problem: He’s Miriam’s father, and when

she appears and gazes at Jimmy with a sincere look of admiration, he simply has

to play the role of the fighter that she so highly venerates.

Admittedly, little, if any, of what I’ve described thus far

is likely to seem all that novel. However, what follows completely defies

expectations. (I won’t spoil it except to say that a miracle cure for all that

ails you and a quote by P.T. Barnum reverberate throughout the film.) It is as

if screen writers Frederick Jackson and Joseph Poland had looked through a

crystal ball and seen all of the cinematic clichés that would follow and made

it his mission to make the one film that was the exception. And in defying

these expectation, they gave MacLean a heck of a role. Admittedly, I was

suckered in by the romance and saccharine sweetness of the opening scenes, ones

that would have been right up Harold Lloyd’s alley. However, that sentiment

changes with the arrival of “Jingo” Pitts, the reporter, another character that

goes against stereotypes. Suddenly, MacLean takes on the demeanor of a spoiled

rich kid eager to be rid of, yet profit off of his father’s life’s work. When

he gets the offer, his expression is of sheer giddiness, akin to a child who’s

just gotten his allowance and is now consumed with thoughts of where to waste

it.

In fact, the role of Jimmy requires MacLean to take on a

kind of split personality. There’s the confident, diligent persona he adopts

for Miriam and the local politicians, and then there’s the nervous, almost rueful

one we get hints of whenever his fellow townspeople are certain to be looking

the other way. This is evident late in the film in one of the best courtroom

scenes you’ll ever see in a comedy. In one of its best moments, Jimmy is

questioning a witness for the prosecution and with a straight face actually

asks how doctors can be so sure that charcoal

causes health problems if they’ve never prescribed it. Jimmy then flashes that “million-dollar

smile” that MacLean was famous for, so proud of his cleverness, only for it to

instantly be replaced by one of embarrassment after he catches a glimpse of the

judge’s stern, disapproving look. The judge is impressively played by Carl

Stockdale.

The ending, alas, comes out of left field and is a major

cop-out. It would have been better for the film to invest in its storyline

fully and perhaps end with a newspaper headline declaring the world to be in

perfect health. Instead, we get a feel-good message about the power of

suggestion that doesn’t gel with what came before. I get it, though. In 1921, we

were in more traditional times. Movies were just starting, prohibition was in

its second year, and people were already wondering if Hollywood was glamorizing

a lifestyle that was anything but Christian. In a way, the ending is a way of

reaffirming those values that so many people said movies should uphold. Still,

it is the most forgettable part of the film.

And so, I return to my earlier impulse – to put MacLean

among the giants. I know it seems premature to make that assertion after just

one film, but think about all those times, you just knew. When you watched an

actress making her onscreen debut and immediately proclaimed she would win an

Academy Award. When you heard a song on the radio and could tell instantly it

was destined to hit #1 on the charts. When you watched a college athlete and

had no doubt he would be considered a legend one day. Sometimes you can tell.

(on DVD from Undercrank Productions)

4 stars

*One A Minute

has been meticulously restored and looks incredible. I may have to rethink my

views on Quickstarter.

*The courtroom scene features one of the most creative uses of Chinese characters I’ve ever seen.

In discussing Douglas MacLean’s 1921 film One a Minute, I’m tempted to paraphrase the tag of Billy Crystal’s 61* and ponder history’s rather peculiar judgment that there were only three great silent comedians of the male persuasion – Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd. The implication, of course, would be that MacLean deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as those cinematic giants, a suggestion that Kevin Brownlow had no qualms about making in his seminal book The Parade’s Gone By, but which I cannot support beyond the deep affection I have for his performance in One A Minute. See, fate saw to it that MacLean would be easy to forgot. Of the twenty-three feature films he made, only two survive in full. Our loss.

*The courtroom scene features one of the most creative uses of Chinese characters I’ve ever seen.

No comments:

Post a Comment