I have a hunch that at some point during a professional

screenwriting seminar, the host gives aspiring screenwriters the following tip:

Make one of your characters rich.

Or, at the very least, make your protagonist come in contact with

someone rich.

Otherwise, you’ll have

a hard time convincing the audience that he can dash off to the airport on a

whim and pay full price for a plane ticket to Paris, a la Jack Nicolson’s

character in

Something’s Gotta Give. And

if such a character doesn’t fit the narrative,

just make a hefty expenditure a symbol of the character’s devotion to

his profession. This explains why a high school teacher can have 30 copies

of a $25 book sitting in his car just waiting for a physical confrontation to

justify his extravagant purchase or why a member of a CSI team can suddenly announce

that he not only ordered and personally paid for a forensic device only available

in the U.K. (imagine the shipping and handling on that!) but also just happens

to have it on hand when only it can solve a crime. Heroes, you see, don’t let a

little thing like money or debt stand in their way.

And speaking of heroes, it’s a good thing that Tony Stark

is a billionaire because otherwise we’d watch the Iron Man and Avengers films

and wonder just how one person was funding the whole operation. After all, the

Avengers need a not-so-secret headquarters, advanced aerial transportation, state

of the art costumes, devices that create an unlimited supply of arrows (until

the plot calls for them to run out, that is), a constant supply of impenetrable

shields, high-tech motor vehicles that can withstand falls from planes, nifty utility

belts, and communication devices so small that it looks as if the Avengers are talking

to themselves. Oh, and an army of remote-controlled Iron Man suits that Stark

has no “financial” problem blowing up as a gesture of his love for Pepper Pott.

I mean, really, that’s one rich dude. And yet, according to

The Falcon and the Winter Soldier, he

didn’t pay Sam a monthly salary. Go figure.

But let us leave the magical realms of comic book

universes and return to depictions of life that are meant to better reflect the

world in which we live, and by this I mean that emotion-filled world inhabited

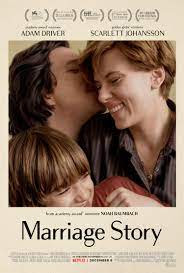

by Charlie and Nicole Barber. Charlie, for those of you who haven’t seen Noah

Baumbach’s

Marriage Story, is a

genius theatrical director, and Nicole, his theatrical muse and wife. In the

film’s opening scene, we learn the two are in counseling ostensibly to save

their marriage, yet it is soon abundantly clear that the best they can hope for

is a cordial dissolution and a nice distance from each other. The two live in

New York and have a son together, and yes, he will soon become the catalyst for

a rather bitter custody battle.

Now if you’ve ever gone through a divorce – and I have -

you know how painful and ugly one can become, especially when property, money,

and children are involved. Many couples start off thinking they can keep things

civil, and a few manage to. For others, divorce and custody battles carry with

them the specter of financial ruin, especially if lawyers become involved, and there

are countless examples of women and single mothers whose standard of living

fell considerably after a separation. In fact, Hollywood used to tell their

stories. Silent films, as well as films from late 1920’s and 1930’s, told tales

of wronged women, of children abandoned or orphaned, of characters so poor that

they became victims of a society eager to take advantage of the downtrodden. It

hardly does anymore.

More often than not, Hollywood gives us films like

Marriage Story, stories in which money

is just a minor inconvenience and large expenses turn out not to be so

burdensome after all. For much of the first half of the film, Charlie is aghast

at just how expensive it is to fly to Los Angeles and back after Nicole moves

there to shoot a television pilot. (She gets the part, of course, thereby

removing any thoughts you might have about just how expensive it would be to

live there.) He even remarks to a lawyer that he can’t afford his services. Ah,

but before you start worrying that he’ll lose custody of his son, know this.

Charlie has been awarded over $600,000 because of his artistic intellect. Now,

the film goes through the motions of having him declare his intention to use

the money to support his Broadway-bound production, but when you have half a

million dollars at your disposal, you sort of lose the argument that you can’t

afford airfare, especially if you purchase tickets well in advance.

The film introduces a “cheaper” lawyer, only for Charlie

to cut him a check for $25,000 and fire him for being “too nice.” We hear that

his Broadway show closed and that with his hectic travel schedule, he “had” to

accept a job directing a few local productions. He clearly feels this is

beneath him, but for most people in his situation, a job is a necessity, not a

luxury that they can badmouth. And then he hires the high-priced lawyer he earlier

deemed too expensive, rents a house in Los Angeles, and directs a local

production and that’s the last we ever hear of money being an issue. As for

Nicole, her repertoire expands to directing, and as her fame grows, all talk of

how she’ll pay for her own high-priced attorney evaporates. In the end,

Marriage Story is a movie about two

financially-secure people engaged in a custody fight, and, as ugly as that

fight becomes, the kid will be fine regardless of which of his parents he ends

up living with.

In other words,

Marriage

Story pays lip service to the real-world effects that its subject matter

has on average folks. Tell the average person that he’ll have to fly to the

other end of the country to see his son, and witness the panic that creates.

Tell the average person that decent legal representation will set her back $100,000,

and take a guess whether she’ll return later to hire his services. How many

average people have the luxury of a television salary or monetary award to fall

back upon? I’m guessing not many. I get it, though. Screenwriters write about

what they know, and successful directors know successful actors, some of whom

go through divorces. With

Marriage Story,

Baumbach has told one of their stories, and in truth, he’s told it well. It

just isn’t

our story, and the sad

thing is that this is likely by design. Even sadder, it’s not likely to change.

After all, which would you rather see, Nicolson and Keaton kissing in front of

the Eiffel Tower, destined for happily ever after, or Nicolson sitting alone

lamenting, “If only I’d had the money!” For Hollywood, it’s a no-brainer.

No comments:

Post a Comment